By the same token over rounding –either by collapse of the muscles in the front or over-tightening of the abs—has the same effect—the spine’s curves serve not only as a container for our interior structure, but distributes strain along balanced curves helping us to handle more impact over time, as well as offering us the flexibility which is the hallmark and gift of human movement. The drawback of this strength and flexibility is that we can bring ourselves to our limits and cause injury, inefficiency and discomfort without anything to intervene and stop us.

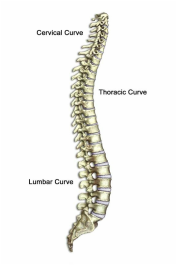

This is especially easy to do in repetitive activities such as cycling. You are calling on your body to repeat its task over and over, and that movement isn't neutral—it is coming out of neutral that makes movement possible (another reason not to ‘hold’ yourself in rigid posture). So this isn’t going to be a blog about how to neutralize your spine when riding, because you can't peddle a bike with a completely neutral spine. However, what I would suggest as an alternative is the idea of ‘resetting’—making sure to give your spine variety and allow it to come 'through' neutral in its motion in order to give you flexibility and ease while in the saddle. Let’s look at this as applied to riding an upright cruiser or hybrid bike first as it is easier to do well. Here you are not as bent over the handlebars as you are on a road bike. Your spine will not have to have more than a cursory bend in the primary(rounded) direction to help you grip—the direction of the fetal curve of the spine you have as a baby, as preserved around your ribs and pelvis. It is important to not allow too much of a sink into this rounding, as that can lead to compression and soreness over time. To help with this, instead of thinking of crunching your abs or bending your front, focus on the side that is lengthening--the long curve of your back. Focusing on this while not narrowing your front and giving your basic directions for your head--neck free, head forward and up in relation to the top joint of the spine-- will create an optimally lengthened spinal curve, which is much healthier than a compressed spine. It is also important to have the seat at the proper height to allow your weight go into your sits bones (the two rocking chair shaped knobs on the bottom of your pelvis) instead of your sacrum (the fused base of your spine), which will inevitably force you into over-curving. The overall goal is to make the spine's natural balanced resting curves the center of your movement--your spine should return through its balanced state (see picture at top of page) occasionally to take pressure off of it. To aid in this, give yourself an occasional arch on the bike to balance out the rounding curve you will probably have in your spine while riding. However, if you ride well, this movement will probably be taken care of naturally. What happens as you turn the pedals? With every stroke of your leg, there should be a naturally curving along one of the diagonals of your back and and arching along the other side. The same thing happens when we walk. To feel this, try taking a step with your left leg--you will feel the diagonal from your left hip to your right shoulder (which should swing slightly forward) round and the diagonal from your right hip to your left shoulder arch slightly. As you step with the right this reverses. The same thing happens on the bike with every stroke of your leg, as it reaches its greatest height (knee bent in front of your torso). One common mistake is to resist this motion and hold the torso stiff thinking it lends stability--in reality, it causes wear and tear on your muscles and joints (especially your hip sockets) and is less efficient. Think of this motion as crawling on your bike--you will even feel a slight push through your hands, though it is important not to exaggerate this movement. It can also be nice to sometimes give yourself a momentary upright twist on your bike to wake up or release these spirals if they have gotten tight or immobile. How do these two principles (moving through a lengthened neutral spine, allowing the back to spiral with the movement of the legs) adapt on a road bike? The simple answer is that they intensify. The strong bend necessary to the mechanics of the bike requires greater head-neck-spine direction, free lengthening of the back, and an ability not to crunch the front. Looking up in order to see the road in front of you can also cause compression in the arch of your spine (using your head effectively on the bike will be the subject of a future blog). To counteract this, I recommend periodic breaks to sit up on the bike, giving yourself a strong balancing arch and a couple of lengthened spirals through the torso. I can't emphasize enough how much prevention is the key here--the more you keep your back from tightening and give yourself breaks before you feel tightness and pain, the better off you will be. That is probably more than enough information for now. Our spines, the mechanism of our primary relationship of movement, will certainly factor into every other discussion of cycling to come. Until next time, Keep Thinking Up!

0 Comments

|

Thoughts on what is going on in the work and the world right now. Many posts to come. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed