|

I am overjoyed to announce the return of limited in-studio instruction for fully vaccinated clients starting Tuesday June 15th 2021 after over a year and a quarter of closure. We are confident that with proper precautions these sessions can not only take place safely but with the quality of relaxation necessary to make them worthwhile.

A couple of details:

In addition to requiring masks, we are implementing comprehensive safety procedures including:

2 Comments

The answer is yes. When it comes to breathing, sometimes less is more. I was recommended James Nestor's 2020 book "Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art" by a colleague because of its deep insights into aspects of the Alexander approach to breathwork and I found many of this book's ideas surprising. It is a highly recommended and refreshingly brisk read (though some of the extreme practices he labels as "breath plus" I wouldn't endorse), especially if you get the audiobook version which includes about a half hour of guided breathing exercises at the end. Here are some of the key insights from the book, with some commentary on how it connects to Alexander Technique work, along with some surprises I encountered. 1. Get Nose-yShould you try to breathe through the nose or the mouth? The Alexander Technique viewpoint is typically that breathing through the nose is more efficient. F.M. Alexander even claimed that doing so "cleaned" the air. Nestor confirms just that. Through exhaustive (literally) and extreme experimentation and research, he finds that chronic mouth breathing is connected to a number of ill effects including fatigue, sleep apnea and other sleep disorders, and cardiovascular troubles. By contrast, nose breathing is connected to a number of benefits including improved energy, rest, and even athletic performance. This only applies to chronic breathing--taking a few breaths through your mouth every once and a while isn't going to have any ill effect. It is about how you breathe in general. 2. All Hail the ExhaleOne of the figures Nestor investigated in the book was breathing specialist Carl Stough, whose work is about jump-starting the the primary musculature of breath--the diaphragm. In order to do so, he created a series of exercises that involve, among other things, an emphasis on extending the exhale. The basic idea is that in order to take a deep breath, you have to fully give up your last one. The results of his exercises were reportedly dramatic: cured emphysema, the restoration of vitality to bedridden people. The Alexander Technique emphasizes the exhale in exercises such as the "Whispered Ah" and the "Silent lalala", and many Alexander Technique teachers (myself included) have incorporated some of Stough's ideas into our basic practices. You can see some of this emphasis in my video "Two Breathing Exercises" I released on YouTube: 3. Slow Down, You Breathe too FastNestor finds that most of us breathe too quickly--we take many more breaths a minute than we need to, and this has a strong impact not only on our lungs but on the regulation of our nervous system. By consciously slowing our breath to a relaxed, even flow we have the possibility of downregulating our anxiety as well as helping our whole system function with more ease. There is even a theoretical optimum breath--five and a half seconds in, five and a half seconds out. 4. Don't OverbreatheEven though this is very much in line with A.T. thinking, I still found aspects of this idea surprising. I work with many of my performance clients to get fuller, larger breathing to support their voices. If you are singing a high "c", a voluminous breath is useful. It turns out that if you are just sitting on the couch, not so much. The reason why is fascinating--too much oxygen isn't great for your system, and carbon dioxide can be. To encapsulate the argument, the easiest thing to do might be to make a metaphor: when you take vitamins, your body can only absorb so much at once. So taking 10000 percent of your daily value of vitamin c isn't super useful. Furthermore, many vitamins have to be taken with other nutrients, such as fats, to be absorbed at all. Think of oxygen like it is the vitamin, and carbon dioxide like it is the fat--carbon dioxide acts as a conveyor for the oxygen that helps your body absorb it. Overly voluminous breaths keep carbon dioxide from being produced, and as a result you cant absorb the oxygen you take in--as counterintuitive as it may seem, you starve yourself of oxygen by taking in too much air. In addition, huge breaths can put your nervous system into "emergency mode" and cause anxiety and other side effects. The solution is to breathe deeply, but in measure--two things that may seem to be at odds, but aren't. The key is having ease of breath and not tensing to pull it in. This works fabulously with each of the last two points--by breathing slowly and emphasizing the exhale, you are unlikely to overbreathe. 5. Holding Your Breath Can Be Good?Perhaps the most surprising thing Nestor espoused to me is that both holding your breath and intentional overbreathing, two things that are not good for you when done chronically, can be therapeutic in short bursts. They can help to train your regulatory and nervous system and have a particularly profound effect on anxiety. He lays out examples of exercises that are best done with a lot of specificity and in a safe place--therefore, I won't attempt to describe them in detail here, but I recommend checking them out. I have tried several since finishing the book and find the breath holding exercises particularly effective. Who knew? Want to explore your breathing and some of these ideas more fully? Check out our upcoming online workshop "Breathe Easy: A One Hour Primer".

,There is an article from The Atlantic written by Amanda Mull making the rounds on social media.

It's titled "Yes, the pandemic is ruining your body: Quarantine is turning you into a stiff, hunched-over, itchy, sore, headachy husk". It is quite the title. I have hesitated to post it to Freedom In Motion's social media (I finally did this Tuesday with the caveat that I was writing a response) despite the fact that it makes a number of relevant points in line with many of the embodiment issues I see as prescient right now. The sedentary, contained lifestyle of the pandemic is causing increased muscular-skeletal issues and side effects on a massive scale. The article is a blues riff that serves the admirable goal of acknowledging that it is not just you who is suffering and bringing attention to a consequence of the pandemic that has gone largely unacknowledged. What made me hesitant to post the article is two things: 1. Mull writes from a place of separation and in antagonistic relationship with the body. The article largely fails to look at the body as more than a piece of machinery that is breaking down and making you miserable rather than acknowledging that it is, in fact you. Perhaps one of the unseen consequences of the pandemic is not just how our body's health has broken down--it is how our relationship with it has changed. 2. Mull has a fatalistic view of the situation. Besides the insight that younger people can perhaps buy a Peloton bike as long as they don't over exercise (which is problematic for a number of reasons--my wife and I got a $115 exercise bike from Target that works just fine), she is pretty resigned to the idea that we are inevitably bound to decline into broken shells of our former selves. She seems distressed that the single yoga pose she used to try to deal with discomfort no longer works like magic. She argues the focus of our action should be on holding our government and society responsible for its failure to properly contain the pandemic (which I generally agree with). While I appreciate the value of an article which makes you feel seen without the expectation of "fixing" the problem (sometimes airing pain without purpose is worthwhile) I also think it is disempowering. The descent, in many cases, is not inevitable. If you care about the future of your embodied self, there are myriad ways that can help and plenty of reasons to not give up hope. Here are just six strategies (there are hundreds) you might find helpful to revitalize you for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond. They might not be able to save you 100% from the consequences of the current circumstances, but they can help you find the middle ground between optimal and ruined. 1. Don't Get Too Comfortable Mull rightly argues that we run into difficulties because all of the small movements we are used to performing in the flow of our normal day no longer exist, leading to stiffness and strain. This is essentially correct. F.M. Alexander argued that no amount of acute exercise could compensate for a lack of attention to the movement of the everyday. The solution for this is counterintuitive for most of us, who seek the most comfy possible home office setup. The problem with a comfy set-up is that it encourages us to move less, and we tend to sink into it and become numb to our body until we eventually move--and feel how much it aches. This is especially true if we set up on the couch or bed. I am not advocating for you to be uncomfortable, but consider having several imperfect set-ups of medium comfort to switch between throughout your day to give yourself variety. When you start to feel uncomfortable, simply switch your setup to somewhere else. Discomfort is usually just a sign that our body is craving movement. Don't ignore it and wait for that discomfort to become pain. The other thing I would advocate for is to not make your setup too convenient. Scattering what you need around your space (even if it is a one bedroom apartment) will force you to get up and move. Whether it is a pen, a water glass, lotion, headphones, your phone, or a notebook not keeping everything within easy reach will force you to get up for practical reasons. Return them to their home base when you are done so you will have to get up to retrieve them again. I once spoke to a CEO of a consulting firm that moved the water cooler further away from a company's employees and turned up the heat a bit to encourage them to have to get up in order to get a drink--it was a bit manipulative, but they managed to reduce employee time out for lower back injuries significantly. 2. Be Preventative, Not Restorative Don't wait for things to start hurting to try to deal with aches and pains--get ahead of them before they begin. Create a morning or midday ritual which features a method to declutter tension in your body and set you up for success--it could be 20 minutes of yoga, simple stretching, or Alexander Technique procedures such as Active Rest (which is excellent for this particular problem). Once you are in pain, it is already too late to work on the issue. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. 3. Breaktime Is Serious Work Schedule breaks at the end of every half-hour (for 3-5 minutes) or hour (5-10 minutes). During that time, get up and move. Use a calendar app or other reminder with a checklist to help you observe these breaks. Treat it like its your job. This isn't just for your body--it's for your productivity. When your body goes to sleep, it takes your brain with it. You become less focused and productive. Start observing these breaks and see how your productivity soars--your employer is unlikely to complain. Also, these breaks are opportunities for other productive bits, which brings us to..... 4. The Value of "Choring" There are probably things that need to get done around your house. Dishes, folding laundry, picking up a room, sweeping, watering plants etc. Use your mini-breaks to get this stuff done. Not only will this leave you more time to rest and recoup in the evening, but these tasks are fabulous opportunities for a simple variety of movement that can get common problem areas such as your hip sockets, knees, and arm joints gently moving. Make it into a little game and give yourself a time limit for each task. Plus, your space will be a much nicer environment to live in. 5. Stop Standardizing Sitting A good question to ask yourself is: "Do I really need to be sitting for this?" If you have a meeting that is based in discussion and doesn't require a lot of writing, rather than having it be zoom could it be over the phone and you go out for a walk-and talk? If you are watching a presentation, can you stand up and move around the room with a pair of wireless headphones? If you have a laptop, can you do a bit of work on your feet? You don't necessarily need an expensive standing desk--a high table, a counter, or in our case a very sturdy music stand can serve as a short term solution to give you some variety. Switching between standing and sitting can do wonders for you. 6. No Means No: Boundaries to Preserve Your Future Self You most likely are not less productive just because you are working from home. Think of all the time wasting things that come up in the office that no longer happen. Firm boundaries on when you will and won't extend your work time beyond your normal hours are crucial. If you make rules for yourself and make them understood to everyone on your team, you are much more likely to keep to them than if they are nonexistent or wishy washy. It doesn't mean that you will never work past 5pm, but what you do shouldn't go beyond your normal in person working commitments. As long as your productivity is within the right limits, you have every right to not feel pressured to overwork. I find a ritual helps with this--I will get "dressed up" for work (nicer sweatpants) and then change clothes to mark the beginning and end of the workday. Or you can get yourself a miniature open/closed sign to remind yourself that you are no longer at work, or move into a different room if you have one. There are a number of ways to mark the change from work to rest, but they are all worthwhile. For more exercises and tips, consider taking an introductory online lesson with me or check out our other blogs and resources. You can sign up for our monthly Uplift email for free resources to help you keep thinking up in your body, even when you are feeling down. 11/9/2020 2 Comments Waiting To ExhaleSince Saturday, I've noticed an interesting trend in conversation and on social media.

Within minutes of the presidential election being called, I saw the same sentiment repeated over and over on my news feed: "I feel like I just breathed out for the first time in four years". Talking with family and friends elicited similar sentiments. Most people seemed surprised that they weren't aware of what they were carrying until the moment it left. There are a couple lessons to take from this: our feelings live in our bodies as physical tension, and when we carry it around for a certain amount of time we go numb to it. Now everyone who reads this may not have the same politics, but I'm sure there is something you are carrying around that is keeping you from exhaling--even if what you might currently be predominantly feeling right now is relief. The way the coronavirus is surging and the lack of effective federal intervention has been covered up by the election cycle but will be in the forefront of our minds within days and there is the possibility of political unrest in the coming weeks and we are all carrying that together. There are people who because of their race have lived their whole lives the way you felt for the past four years. Don't go blind to it. Don't go numb to it. Don't live without processing it. Use it as a spur to action. Use it as a window into empathy. Use it as a prompt to take care of yourself. Don't wait until circumstances change to remember to breathe out, though a full exhale might not be possible. We are never fully free of what we carry, but we have to let it move through the best we can to see clearly and to function as we must in order to heal the world You need the exhale to make the inhale happen. 10/5/2020 0 Comments Missing TouchTo say touch has been an integral part of my life for the past eight years would be an understatement. Since I began my training to do Alexander Technique work between lessons as both student and teacher I have been spoiled by an abundance of touch in my professional life--let alone the touch of friends and family in simple forms such as hugs.

More than six months into the pandemic I feel starved for this most essential of human contacts. Why does touch matter? What makes it different than the other senses? Why does missing touch feel so personal? In an effort to understand I have begun reading David J. Linden's book "Touch", and it has gone some way towards explaining my touch-deprived ennui. Our sense of touch is the first sense to develop--it begins in our mother's womb before we actually formally come into this world. Receiving touch in our early stages of life makes a huge difference in our sense of security and belonging, as well as our ability to empathize with others. I am not sure this ever goes away--even as adults I think touch somehow buoys us to others and the world around us. Part of me wonders if the remarkable untethering of the world right now has been augmented by our necessary lack of physical contact with other folks. The apparatus that comes together to form our sense of touch is epic in its scope. Our skin can weigh upwards of 16 lbs and covers an area of almost 22 square feet. We have two different main types of it, with very different characteristics. Because our sense of touch extends throughout our entire bodies, our sense of ourselves literally comes from touch. The complex receptors responsible for sensing touch come in several types, each which give a particular type of feedback--some sense the contour of touch, others the pressure, others temperature, still others minuscule waves that help us know how hard to grip an object and how to adjust that hold. Others can sense into objects we make contact with to find their deep inner workings (like feeling a door unlock when you turn the key). All of this information is carried by a stunning network of nerves to the equally complex and multifaceted touch map in our brains (see my previous blog about body mapping). Perhaps most presciently, this information is then synthesized with our other senses and past experiences to make our perception of touch completely individual--the exact same touch can be interpreted in wildly different ways depending on who is receiving it and contextual circumstances. We each move through the world and communicate uniquely through touch and intercontact. In Alexander Technique, touch is a tool that draws upon and imbues everything above: security, connection, perception, identity, empathy, a chance to examine our biases and perspectives. It gives us information and experience that allows us to better know ourselves and help all of the different parts of ourselves come into unity. It is both a catalyst for change and an anchor against the tempest of the world. Though Alexander Technique has plenty of value beyond touch (as anyone who has come by one of our online classes can attest), I miss it. In person lessons are unlikely to resume soon, as there is no safe way to be within the same airspace which touch in an A.T. context requires, and with the virus potentially rising again through the colder temperatures we must do everything we can to support our mutual health and fortitude. The distance is necessary. When I write, I usually like to have something practical and actionable for the reader to do with what I have to say. I am not sure what exactly it is within this context. Perhaps, like so many things we lack right now, it is an invitation not to take the wonder of our normal for granted. If you are lucky enough to be in a bubble with someone, perhaps it is a call to not take their touch for granted, and to know you may be one of the sole touch providers for someone else (offering someone in your bubble a massage right now can be an act of life changing generosity). Perhaps it is a call to recognize that part of you is asleep without this contact, and that something IS missing, and that everything you are feeling is okay. And that waking your body up and being in relationship with it is extra important right now. I hope we can be in Touch soon. Learn to integrate your body and mind so you can thrive. Our new weekly set of online group classes aim to get you into your body from the comfort of your own home (or wherever you are). We will be offering three types of online classes starting the first week of September, two on an ongoing weekly basis and another twice every month. Classes are available a la cart or as part of two different types of membership packages/subscriptions. We will be having a free one hour Online Open House on Friday August 28th at 5pm where we will be sampling a bit from all three classes and answering questions on our new programs and memberships. Classes are available for sign up now! Memberships will become available starting Monday August 31st. Read more below to find out about all of the different classes and options! ClassesWe are offering three types of classes online starting in September, and will look to expand our offerings as we go. To see a complete calendar of our online and in person classes click here.  Online Embodiment Group--Wednesdays at 5pm Weekly Starting September 2nd Our Online Embodiment Group gives you access to practices that improve your well-being in every aspect of life and the consistency and community you need to implement lasting change. Meeting Wednesdays at 5 pm CST for one hour, each class will focus on building a different set of embodiment practices and use them to help the whole group grow in a playful, non-judgmental . Sessions are primarily Alexander Technique influenced but will also draw from a variety of other embodied arts and will occasionally feature guest instructors who are experts in their fields. $20 per class. Included in both our Core and Expanded Memberships  Community Lie Downs--Fridays at 5pm Starting September 4th Join us for a 30-minute live guided Alexander Technique semi-supine lie-down meant to help you to leave the tension of your work week behind and start your weekend off on a relaxing note. $10 per class. Included as part of our Expanded Membership; One per month included as part of our Core Membership.  Embodied Performance Salons--Sundays at 3pm Every Two Weeks Starting September 13th Want to integrate Embodiment work into your individual craft in a safe, supportive environment? Our Embodied Performance Salons offer the opportunity for individual coaching and learning from the diverse ways in which Embodiment improves performance from your peers. Great for music, theatre, and dance audition and performance prep, public speaking coaching, workshopping new material, or as a supplement to our Online Embodiment Group. $20 per. Included as part of our expanded membership. Membership Packages/SubscriptionsOur Monthly Memberships are the best way to access a variety of Freedom In Motion classes and content all for an affordable monthly price. We currently offer two levels of membership that cater to different needs, available in either one-time or subscription formats. Both will be available for purchase starting one week before our first class is offered. Core Membership--$75/Month ($90 Value) Our Core Membership gives you access to all of our Embodied Exploration Group sessions of the month (including video for those you cannot attend live), as well as one Community lie down and special short video and audio content releases. A great value you can use to grow over time! Includes: Up to 5 Online Embodiment Group Class Sessions/month (depending on the way the calendar month falls) One Community Lie Down/month Special Video and Audio Content Releases Expanded Membership--$100/Month ($150 Value) Our Expanded Membership allows you unlimited access to our online classes each month, including our Embodied Exploration Group, Community Lie Downs, and Embodied Performance Salons, videos of any classes you can't make live, as well as special content releases and other extras. Includes: Unlimited Online Embodiment Group Sessions/month Unlimited Community Lie Down/month Both Embodied Performance Salons/month Videos of all sessions Special Video and Audio Content Releases 1/6/2020 0 Comments VulnerabilityDoing something new is hard. Doing it in front of 23 college freshman is terrifying.

A couple weeks ago I taught my first college class. Even though I have five years teaching experience, I still find new material and new settings difficult--it is essentially an experiment that what I bring to the table will have value for those I am working with, and as these people have usually made a fair commitment of time/money to be there I usually feel a lot of pressure. This was something entirely different. Being in a college classroom at the apex of a five year plan that had somehow actually come through I had a tremendous amount of impostor syndrome. I found my whole body tightening up, my words flowing poorly, and my breath not connecting in my usual way. I don't think I did a bad job through the first week, but things didn't feel quite right. The second week, I had a two hour class alone with the students without my co teacher. As I stepped of the red line and turned towards the staircase, I stepped on an invisible puddle that had condensed from a pipe above the platform. It was a completely friction-less surface. My foot immediately went out from underneath me and only my other foot shooting out into a quick, stage-combat influenced lunge saved me from some pretty bad bruises. This experience had a strange effect--rather than unnerving me, it shook me out of a state I hadn't realized I was in--all of a sudden, it seemed strange to want to keep any sort of dignity after publicly taking a pratt fall. I had an epiphany--the reason why I felt I was struggling in class was because I wasn't allowing myself to be vulnerable. One off my default habits when I am in a new situation is to try and present a very put together, authoritative front. During my training as a teacher, my trainer noticed this habit again and again and instilled in me that not only does this sometimes block me from making my full humanity available to my peers, but it had a disentigrative effect on my Use--the level of ease with which I employ my body. It is actually the fear of being vulnerable that causes me to tense up to try and present an impression of competence--this actually blocks me from being as competent as I can be. My fear of being exposed becomes a self fulfilling prophesy. This tension also keeps those around me from being comfortable with their own vulnerability--I am essentially demonstrating that they themselves shouldn't feel free to open up. My fall helped my mask to slip, and I realized that I didn't need it anymore. I decided to try a different tactic--rather than trying to teach well, I asked myself if I could teach vulnerably. The effect was transformative--immediately I had a completely different presence in class, and I could see the students immediately respond. Its not something I can do all the time--especially at the beginning of classes, I still feel that push in myself to present a front. But if I take some time and try to soften up, I find I can navigate my way to the gift more often than not. The amount of energy we use to resist being vulnerable is enormous. The magic is that if we allow ourselves to open up, the need for that protection often evaporates. This is something I will always work on. If you want to explore your own ability to be vulnerable and present, consider joining us for 'Exploring Presence and Vulnerability with the Alexander Technique' March 15th at Green Shirt Studio. You can also build your stamina at performing in front of others at our Group Performance Coaching Saturday February 29th at Pendulum space. It's the New Year, which means many of us are looking to get our butts in gear and work towards our fitness goals.

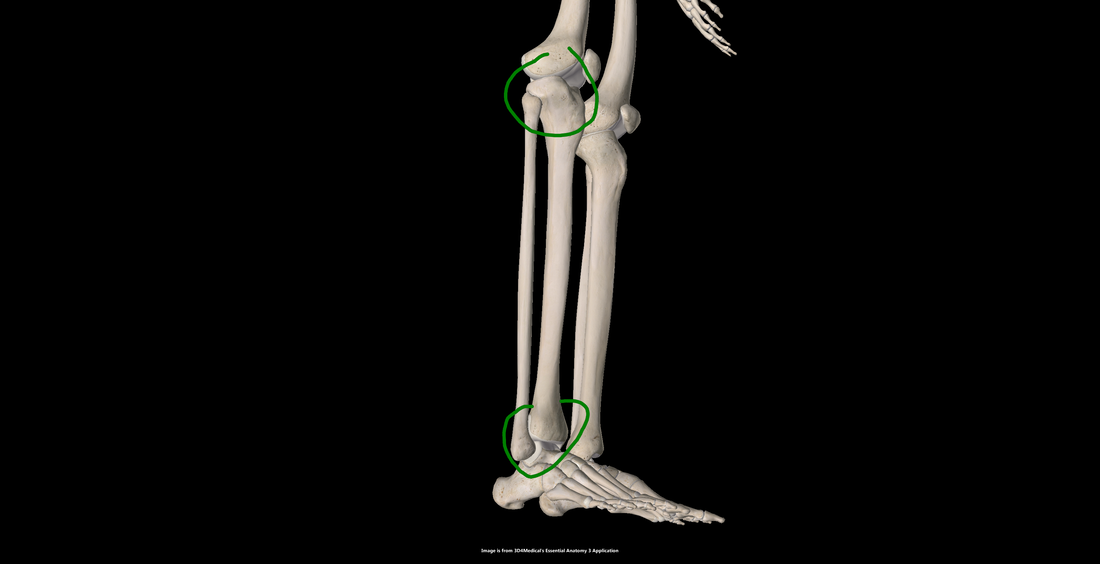

Since so many folks are hitting the gym, I thought it would be worthwhile to talk about some of the differences between moving when you work out and moving in your everyday life. Many well-meaning fitness instructors will show you an exercise and say "this is how you_______". Sometimes that is true, sometimes it isn't. It is easy to accidentally form a conception that how you strengthen your body is the same as how you use it, but that simply isn't always the case. Almost by definition, fitness involves putting a strain on your system and muscles that is somewhere near the edge of it's capabilities. Similarly to how we learn, moving into this space is the only way we grow--using ourselves in this fashion activates the mechanisms that lead you to build new muscle, improves the efficiency of your cardiovascular system, and can do many other things to improve your fitness. There are a few ways effective exercise classes do this. All of these methods can be fun, challenging, and enriching for the purpose of improving fitness. However, lets look at what happens if we transfer these ideas outside of the gym, some of the issues that can come up, and how to solve them: 1. Adding Weight Issue: we often create what I call "effort appointments" for different activities. You can think of these as the habitual amount of energy we spend to do any given movement. When we do a lot of weighted workouts, we sometimes develop a habit of approaching a given movement with the effort it takes to do it when weighted rather than what it actually requires in the moment--essentially we go through life at "maximum effort". This can be exhausting, burn us out quickly, and sometimes lead us to excess tension that can undercut us in various ways. Solution: A good way to think of the benefits of strength training is that we are trying to gain strength so that we have it available to use when necessary, not all of the time. You can use an "effort scale" to rate your movements and how much tension you are putting into them: if you are turning a doorknob at a "7", you may be using more of your strength than necessary. For most everyday movements, a "3" is about right--not too much tension and not too little. If you get used to rating your everyday effort, you will start to gain context and will be less likely to overwork yourself by over-activating your muscles. 2. Pushing Movement Pace Issue: We sometimes hold onto a fast-moving adrenaline state when we spend a lot of time doing cardio work. When we get used to moving fast a number of things happen. Our system becomes very stimulated, and we may tense up in an effort to maintain the quick pace we feel--so we end up using more effort than necessary. You may hold your breath. Quick tempos are often associated with un-useful stress--you may notice your ability to think effectively decreases and you become more reactive. You may make mistakes if you get used to moving too fast, leading to more work to correct things. Generally, when our internal tempo gets miscalibrated we end up feeling rushed and unsettled. Solution: Similar to the solution to "Adding Weight", you can use a "time scale" of 1-10 to notice when you are moving faster than you need to and slow down. It can also be very useful to consciously pause for a moment before doing various movements--this opens up space for breath and ease in whatever you do. Plus when something actually requires moving faster, you will have saved the energy to do so effectively. 3. Changing Form Issues: This is perhaps one of the most potentially perilous aspects of fitness training. When we change forms in fitness classes, it is often to make what we are doing less efficient--this puts our muscles in a position where they have to work harder, especially if we are trying to isolate a certain muscle. Our system usually functions most effectively as a cohesive whole with all of our muscles working together to counterbalance each other. Without this, we are simply working too hard in everyday life. What makes it worse is that emphasizing certain muscles can add unintentional strain on other parts of the body--if we move this way in our everyday life, we can risk injury. Solution: Learning about what different exercises are intended to do! This will help you to select whether you want to move that way in everyday life (many fitness instructors are great at integrating this into their classes). Integrated movement strategies such as those learned in Alexander lessons can help you to find the most useful forms and strategies for your day to day life. Remember, there are no inherently bad movements--it is just about figuring out what is serving you best in the moment. 4. Compressing Into Movement Issues: This can be one of the most potentially harmful affects of translating fitness movement into our everyday life. Instructions such as "engaging your core (covered in another blog)", "pull your shoulders back", and "pull your thighs together" can cause you to habitually compress your body in movement, leading to wasted energy, tension, lack of flexibility, injury risk, and an overly-rigid approach to your everyday life. Solution: Much like our approaches to Adding Weight and Changing Form, it can be very useful to know how these instructions can be useful in a strength building context but potentially destructive in the context of everyday life. Have the strength, but only use it when necessary. Alexander Technique teaches you to cue lengthening as a prerequisite to movement and as such can be a direct antidote to over-compression in movement. Picture this--you are about to step in front of a huge crowd to deliver the speech of your life. Naturally, you are a bit nervous. You stride out onto the stage, turn to face your audience, and.... What happens to your legs? If you are like 90% of my clients, your knees lock. This may seem like a small thing but it has far reaching consequences. When your knees lock, it is a symptom of the whole body locking. As a natural consequence of this small action a cascade of things happens to you: you tilts slightly backwards, bringing you off of your center of gravity and putting all of your weight on your neck and back. The back of your legs and glutes tighten to keep you from falling backwards, your head tilts back, and your shoulders tense in an attempt to brace you. This has subtle but deep consequences--your breathing becomes more shallow and is forced into your chest and your larynx tightens against your throat, constricting your voice. Your face takes on a strained quality, and you realize you are leaning subtly away from your audience. They feel distanced from you. You start to feel a nervous sensation. You try harder, and find that your arms fly up in front of you and you begin to gesture distractingly. You are caught in a Tension Loop. Tension Loops happen when a response to stress cascades from one part of ourselves through our whole body--and when we try to correct the problem we end up sinking further into it. Often this is because we are trying to treat the symptom--tense shoulders, shallow breathing, strained voice--rather than the cause. For many of us, one of the major causes of a Tension Loop has to do with locking our legs--often a well-intended attempt to stabilize and ground ourselves when we are nervous. We often feel this as our knee locking, when it is actually our whole leg. When this happens we lose the natural support system of the lower body and the upper tenses to compensate. If we realize our knees are locked and try to unlock them, a funny thing happens--for many of us, we actually end up breaking apart at the spine just above the pelvis instead (as in the person below). We sometimes identify this as a tilt in our pelvis, when it actually is a symptom of the joints of our legs being locked. So how do we actually solve this problem, unlock our legs, and relax into the support of the ground? The magic key to unlocking your knee is your ankle. Unless we have an injury, most of us don't really think about our ankles often. They are one of the joints that are furthest from our head, so most of us aren't used to relating to them. But all of the joints of the legs are inseparably interrelated, so it is impossible to unlock your knee without unlocking your ankle first. Why? Take a look at the picture below. You will notice that the ankle and knee are two ends of a lever--very simply, if the ankle is locked, the knee locks with it and visa versa.

The plus side of this is that if you unlock the ankle, the knee will magically release. This "how" is unfamiliar but simple. You may tell yourself you don't know how to unlock your ankle, but it is easy--just think of releasing it a little bit. Since it is the foundational joint of the body, when it lets go all of the other joints automatically adjust. Most people find their knees will release without trying when the ankle does and they will immediately feel their body settle into a sense of groundedness. With this groundedness the upper body is able to relax and is free to move and express. (NOTE: it is important as you release the ankle to keep a sense of connection in your spine, so your whole body does not collapse as well) This one simple idea can transform performance. It helps you to relax, find your flow, and put your best foot forward. Next time you are performing or even are just standing around, try this out and see what it gets you. 1. Elasticity Is EverythingWho doesn't want some free energy? The Art of Running is all about getting more out of your running with less effort. To do that, the method takes advantage of something called Elasticity--loading muscles to stretch them, and then getting a free bounce off of the release of the contraction. Most of the specific points of the method--getting the foot to make solid contact with the ground, increasing stride length and width, pelvic and rib movement, how to 'bounce' off your feet on each strike, and even the inclusion of your arms in your running are all aimed at maximizing this internal force. It can be elusive to tap into, but when I found it I had this wonderful feeling of the body 'running itself'--all I had to do was sit back and enjoy the flow. 2. It's Okay to Go 30%As someone who finds running to be a challenging activity, I have long done what most people do when they encounter an activity that is difficult for them--I try harder. I learned though this training that my effort appointment for running is way more than is useful for me--I put so much into it, it is really hard to access and take advantage of any natural Elasticity in the body. To help with this, I received the advice to try running at 30%--enough that I wasn't under working, but also enough that I could concentrate on form, calm down my legs, and start to feel Elasticity helping me out. Now that I'm getting more used to it, I can concentrate on maintaining the 'feel' of the running while slowly filling the form with more velocity. 3. Practice Intentionally, Run MindlesslyOne thing was crystal clear from the training--there is too much going on while running to try to control every element consciously. In fact, if you do, you are most like to gum up the works and interrupt the natural flow of your run. So, it is better to take one specific element at a time, work on it intentionally through specific exercises, and then let it filter into your run and don't worry about it. This one at a time, alternating mindfulness and mindlessness approach is a great way to improve while enjoying the fruits of your labors at the same time

|

Thoughts on what is going on in the work and the world right now. Many posts to come. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed