|

7/29/2019 0 Comments Podcasts and PresenceI hate running. I have since I was a small child.

I used to fake sick every Friday in middle school when we had to do a mile run. People would make fun of the way I looked when I ran. I would have trouble breathing, and was slower than everyone else. Fast forward 20 years. In a week I will be taking an intensive training program to teach others how improve their running, and what’s more important: to actually enjoy it. I first started running more seriously while at an arts summer camp before my senior year of high school. They woke us up with a bugle call at 6am (I know, right) and there was a big gap between that and our first class for breakfast. However, I hated the food. There was a big open field behind our cabin. So, I decided to go for a half hour run as many days as I could that summer. I cranked my first MP3 player (or possibly a Discman) up to full blast and ran around the field for an unknown distance before collapsing back in my cabin for a quick shower. I still hated it. What made it work, the only thing, was having music I was excited to listen to. Fast forward again to the last couple years. After a lot of experimentation, I have found that one of the things in my life that leaves me with the best vitality is running consistently. Every period where I do so corresponds to the best periods of health in my life. The run however, is still a chore. I do my best to check out during the actual ask--I see it as a time where my mind can wander. I get caught up in the music I’m listening to, or as has been the case recently, podcasts--ironically, many of them are on the Art of Presence. Fast forward(er) to a couple months ago. I’ve signed up for the ‘Art of Running’ teacher training and am reading back through Malcolm Balk’s book of the same name, when I reach a bit that terrifies me. In the book, he advocates for running without any music or audio. This allows you to pay more attention to your body and turn the activity into a form for enjoying the present moment and getting more in touch with the sensation of being embodied—the exact opposite of the routine that has allowed me to successfully be a runner for the past couple of decades. Why does listening to audio take us out of our sense of embodiment? It is hard to say exactly. There are curious connections between our sense of embodiment and our sense of hearing. When I do spatial awareness exercises with clients I often tell them to ‘listen’ to the space around them. We ‘listen’ to our bodies. And there is something about sustained artificial audio that takes us out of our bodies and can give us a sensation of floating in an intellectual space outside of our embodied reality. Reading this, I realized running is one of the activities in which I ‘kick myself out’ of my body almost completely. And the idea of coming back into my body when I run brings back old terrifying associations with shame over being made fun of for ‘running weird’ and other body shame issues. Grudgingly, I decided to try it out. The results have been startling. The first striking thing is that I immediately set personal records at the three distances I run most frequently. And not by small margins—I improved 2 minutes on my mile run and nearly 10 on my three mile. These are HUGE. They are probably a result of me better being able to pay attention to mechanics, and more importantly, to feel when I was approaching an unsustainable level of stride and stay on the edge of it rather than going over and then wearing myself out, forcing me into interval or below pace running. Secondly, I found I was less worn out after runs, and actually enjoyed them more. They made me feel great in my body when I stopped avoiding the experience of being in my body during them. I found myself more energized for the rest of the day, with a great sense of the support of the ground below me and the movement in my hip sockets. This made me curious about the way I consume audio in general. I love music and podcasts, but sometimes it just ends up feeling like a background buzz that I’m not really paying attention to. So I made an experiment—what happens when I don’t allow myself to multitask with audio while I carry out my daily activities? Once again the results were shocking to me. Suddenly, all the activities that used to be dreary chores became interesting to me again—opportunities to make friends with my body. My posture improved in all of them. And when I did listen to music again, I felt like I was really hearing it rather than just using it as a way to check out. The moral in the story from my perspective is not that listening to podcasts or other audio while doing your daily activities is bad for you. Its simply that when we do too much of it, we lose the ability to be present in any of what we are doing. And if I even do one activity a day without my normal audio, my quality of life improves. Here’s your challenge: pick an activity you usually supplement with audio. It could be running, it could be doing laundry, it could be driving. And try doing it without sound for a week. How does your relationship to the activity change? How does your relationship to your body and posture in the activity change? How does your enjoyment in the activity change? Let me know what you discover!

0 Comments

“Worry is a misuse of the imagination.” “It’s dark because you are trying too hard. I am a performer. And I suffer from anxiety.

I came across the first of the two quotes above awhile back and was immediately struck by it. What it highlighted for me was that when I was using my imagination onstage and when I was worrying, I was using the same muscle. Throughout history, anxiety and imagination have been tied together through countless artists who also suffer from difficulty creating healthy boundaries around their creativity. Creativity itself is a neutral force that can be used for good or evil, self-realization or destruction. When I was in theater school, I struggled with over-effortful performance. A professor told me I had tremendous energy and needed to find a better way to channel it--it was like a fire hose that had so much pressure that it lost control. This need is what forged my original connection to the Alexander Technique (I've written a bit about my personal journey in other blogs). Through A.T. I found a way to ground and direct the stream of my thoughts and energy to benefit me rather than harm me. Through this I shed much surface tension and anxiety and greatly expanded as a person. But there has always been a holdout of these energies that have persistently resisted being dispelled. Recently I've had a breakthrough in how to take my work with myself(and students) even further. It has to do not just with the Direction of my thinking, but with the intensity of it. A tool I use often with students is the idea of the Effort Scale, which I adapted from teacher Joan Schirle--the idea of analyzing any movement on a 1-10 scale of effort and trying to find the appropriate tension for what you are doing at any moment. Sometimes extreme low or extreme high tension is appropriate, but often right effort falls somewhere on the 3-5 range. Usually we apply this physically, but lately I have been experimenting with it mentally--how effort-fully am I thinking? I was shocked to find that even with improvements to my day to day physical effort, my mental effort was still often higher on the scale than I would have thought, and that certain activities, especially those where I use my imagination, spike this effort higher still. This made me think of the Aldous Huxley quotation at the beginning of this blog. What if I could think lightly, but still deeply? How would that change my anxiety? How would it change my performance? The early results have been pretty mind-boggling. When I feel anxious, i don't try to stop thinking anxiously--instead I try to think lighter (somewhere on the 3-5 range on the scale). And I've found my anxiety has had significantly less hold on me. When it comes to performance, specifically acting, more nuance and ease has been communicating with less of a tendency to get stuck in my head. Its been like a magic trick. Next time you feel tense, try thinking lightly but deeply, and let me know how it goes! This is part 1 of a new series of blogs on how to learn anything more easily and get the most from your Alexander lessons Have you ever heard the story of Goldilocks and the three bears?

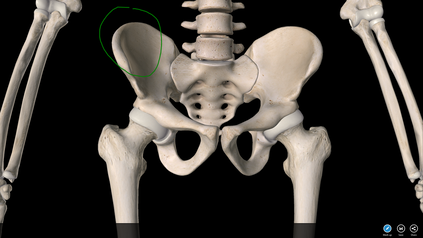

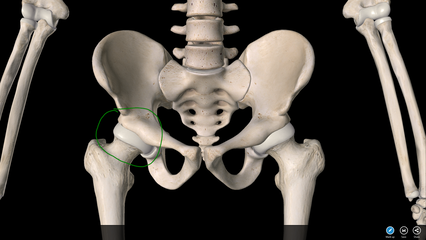

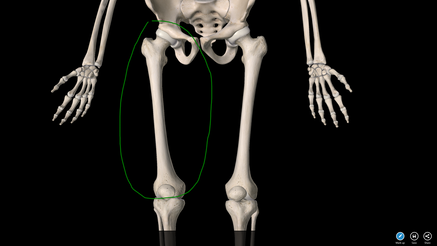

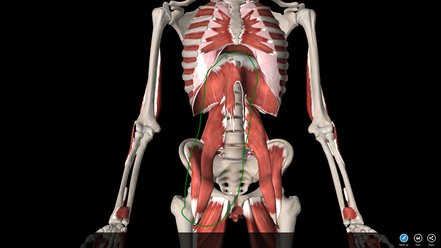

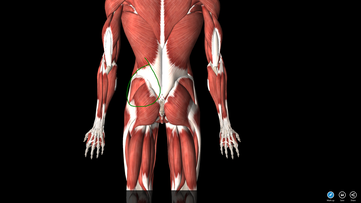

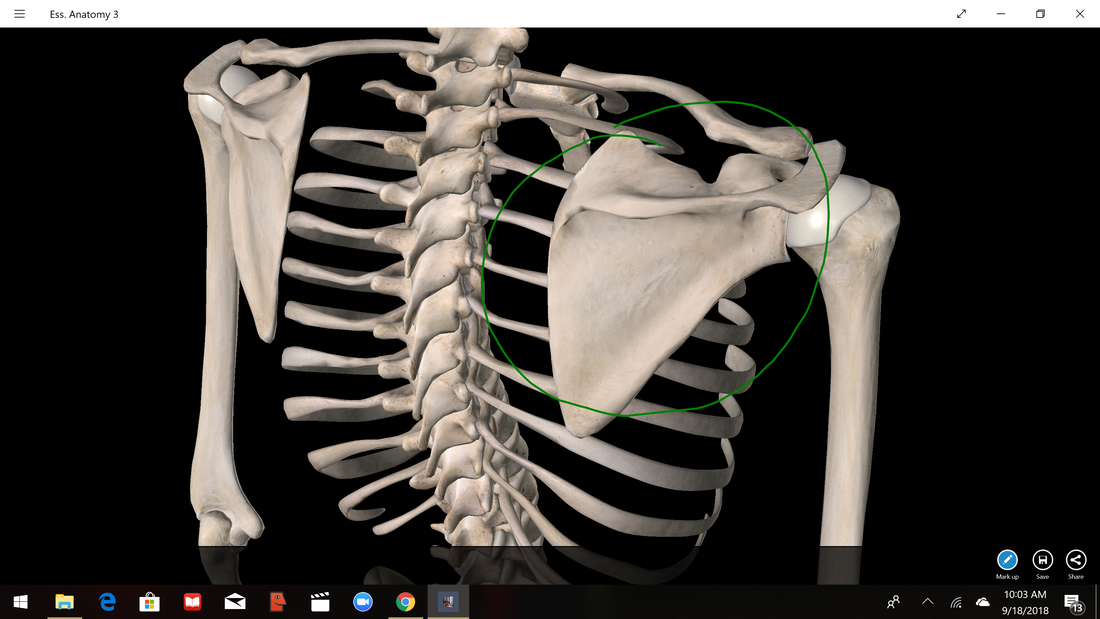

A young girl comes across a cottage in a woods and decides to go in. She finds three bowls of abandoned porridge. She tries one, and astoundingly it is too hot (despite being left alone presumably for at least a couple of minutes). She tries another, and it is too cold. The third bowl is just the right temperature. (It is best not to overthink the physics involved in this. Did they spoon out these bowls at different times? How do bears hold ladles?). She then goes on to repeat this process with chairs and beds, trying out wrong options until she stumbles upon the right choice, before being surprised by the houses' three occupants and running out (probably unnecessarily--from their choice of furniture and food, it is obvious these bears are more interested in comfort than aggression). Like most fairy tails, this story is not really about what literally happens in it. What can this teach us? Is it about the dangers of turning to a life of home invasion and food theft? My take is that one of the things this short, complex tale is about is how we learn. How does Goldilocks find what is 'just right'? By trying out the too hot and too cold options and settling on something in the middle. When we are learning to do any activity, we typically don't follow this process. We aim to get the result directly--by trying to find the 'right' option for us as quickly as possible. The right amount of tension. The right way to do something. We judge what is right by habit and instinct rather than informed choice, and often hamstring ourselves as a result. A technique I have found more useful is to try out extremes and use them as a basis to form discernment of the best choice. A good example is an experiment I do with every student in their first lesson--I have them try out a slump (collapse), a strut (overly effortful posture), and then go for something in the middle--if it is somewhere between these extremes, they can trust they are trending in the right direction even if it feels unfamiliar. With time and repetition, this helps them build up their sense of poise until they become quite skilled at selecting the right tension for any activity. Similarly, you can apply the Goldilocks principle by intentionally trying out 'wrong' options for any given task-eventually you gain a sense of what the right options must be. One of the keys about this idea is that it no longer becomes about whether you are doing something right (a moral judgement), but about accruing experience. This can take away a lot of the pressure we put on ourselves. I am excited for you to try this out on your own and to see what you discover! 1/4/2019 1 Comment 5 Mind Blowing Tips for HipsOur hips are one of the most important joints in our bodies and one of the most overlooked. Here are 5 keys to unlocking their full potential. 1. Your Hips Are Not Your WaistWhen I do workshops and ask people to point to their hips, most people point to the tops of their pelvic crests at the level of their waste, approx. here: The issue is that there actually isn't a joint here. In fact it is one of least flexible parts of our spine. From an anatomy perspective the waist doesn't exist, yet many of us unknowingly try to bend from there. The true hips, the hip sockets, are here: As you can see, this is quite a bit lower and more towards the interior of your pelvis than you might have thought--a couple inches towards the center of your pelvis from the buttons on your jean pockets. Try bending with this idea in mind--how does it change the movement to think of bending from here rather than the waist? 2. Hips Gotta RollOne thing you may notice looking at the above picture is that your hips are not a hinge joint (like your elbow) but are a ball and socket. What this means is that whenever your hip joint moves it moves in multiple dimensions--it rolls out as it flexes, and moves back towards the center as it straightens. What this means practically is that your knees will also naturally float away from each other subtly as you bend them. We often use excess tension trying to hold the knees together and keep the hip socket from rolling rather than letting it go through its natural range of motion. And on that note..... 3. Hips and Knees Are BestiesOne of the things that can cause us problems when we move is working with parts in isolation rather than looking at the function of the whole body, the whole self. Lets look at the hips and their besties, the knees: The most important thing to notice here is that they are not in fact separate structures--the plug of your hip socket and the top of your knee are all one bone. What that means is that when the knee moves, the hip must move. This is key to understanding bending, walking, and many other activities. If you try to move one without attention to the other it might go poorly, and many of us will unintentionally bend at the waist instead. 4. Your Hips Have A Lot To Do With Your BreathingMany of us think of our breathing being a function of our lungs, chest, and throat--in fact it is a whole-body process! Check out the connections between the hip socket and the diaphragm--the primary muscle of breathing. You will see a muscle called the Psoaz that links the two. When your hip socket doesn't have free movement, it affects the movement of the diaphragm. Wa-pow! 5. Your Hips Are Not The End Of Your LegsFinally, we think of our hips as the end of our legs, often dividing ourselves into upper and lower bodies (sometimes at that imaginary waist we talked about earlier). Surprise! The functional network of muscles that are part of the motion of our legs extends all the way up to the lower back, where they overlap and interconnect with the muscles of the upper torso.

So in reality we all have legs for days. How does it change your thinking about your movement if you imagine your legs extending up to your lower back, and your hip socket is a middle joint rather than an ending joint? 12/19/2018 0 Comments Slowing Down and Speeding UpThe holidays are upon us. For the next couple of weeks we have the rare opportunity to slow down, be present, and appreciate life.

My hope is that when someone comes in for an Alexander lesson they get a miniature of this experience. Much of we what we do in A.T. work is slowing down our patterns so we can be aware of them and make changes if we wish to. It provides a delicious opportunity to come back to yourself. It may or may not surprise you to know that I have quite a bit of trouble slowing down. My impulse is always 'go go go fast fast fast'. That's why this work provides such a valuable balance for me. It allows me to make sure that I am not outstripping myself and missing the forest for the trees, or working against myself without knowing it. I can similarly find holiday times frustrating. I struggle with truly taking the phone off the hook. One thing that helps me is the consciousness that moving slow actually enables moving fast. Without pauses, I wouldn't have the energy, stamina or focus for when things are really going. I discover things in the stillness I wouldn't otherwise see. At this speed I can practice and build the skills that will serve me when things accelerate. Alexander work can feel like we are seeking to slow you down quite a bit, and sometimes students mistakenly think that it means you are supposed stay slow. That simply isn't true. The truth is, you go slow so that you can go fast. You can only do quickly what you have taken time to build through patience and care. Perhaps this an interesting way to see the coming holiday. Rather than waiting for the New Year, when things wind up to a fever pitch, to make changes, what if you start building for what is coming while things are slow? While things are still? While you have choice, and presence, and ease? Perhaps that is the true way to take a holiday and make it last all year. 11/27/2018 0 Comments Reactivity, Automation, and ChoiceAccording to Alexander Technique ideas, we have three choices at any given moment of time:

We live in a reactive world, and one that prays upon and is custom engineered to profit from it. From the cable news cycle to the ads in our news stream on Facebook, our world is not only automated but built upon the hope that we will be as well. See a news story? Feel angry. Click. See an item custom designed from an over-intimate knowledge of our google searches? Buy it. Alexander worried about the impact of automation on our lives all the way back in his first book Man's Supreme Inheritance and drew strong connections between this and the turmoil and proto-facism of the first world war. In this increasingly automated world, it is easy to feel like you don't have control--that you are being pulled inexorably and helplessly down a conveyor belt that is built not for your own happiness but for that of others. And while some of these features are sold as designed for convenience, I do not believe they lead to fulfillment. I believe it is the agency of our exploration that gives us pleasure, not the decisions themselves. It is only with this agency that we can be awake to the miracle of life around us. So how can you practice this freedom? By questioning your responses and practicing non-reaction. If you see that political post on Facebook, ask yourself 'what if I am wrong about this? How could I respond differently?' Then try it. If your initial impulse still feels right, then you will know your conviction is sticky and that you are making a choice, and not just reacting. You might discover the new idea opens up new possibilities of empathy and action. You may also ask yourself whether you need to respond at all. Of course sometimes this is impossible, but even a slight pause in response can loosen a reaction to the point where you can make a considered decision. Even if we are right on an issue, we need to ask if our initial response is helpful or part of a system that creates the conditions we abhor. I cannot emphasize enough that this is not a process of creating false equivalencies between facts and opinions--it is simply a way of distinguishing the difference for ourselves and examining our processes of action. We do this in A.T. lessons every day. By making simple decisions on whether to move in a habitual way, a new way, or not to move at all, we are subtly strengthening our power of choice over our lives overall. That's why we are called Freedom In Motion. You may choose to take this advice. You may choose to do something different with it. Or you may choose to do nothing at all with it. The choice is yours. A couple of weeks ago I had the opportunity to join the Poise Project's Chicago training for working with people living with Parkinson's and their care partners hosted at the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab. A wonderful day with colleagues learning how to better serve this community. Check out the photos below for a look in!

'ENGAGE YOUR CORE!!!!!'.......your fitness instructor, yoga teacher, or coach yells at you, half frowning, half grimacing with delight. * What do you do? If you are like 90% of the people I have worked with, you will immediately tighten your outer abdominal muscles. What happens as you do this? You might notice that immediately you stop breathing, your neck tightens, and your shoulders fly up. Surely, this can't be what your friendly instructor wants. Why then would they ask you to do this? The reason is that the word 'core' has been like a magical fitness button that has been pressed endlessly over the past three decades in fitness culture. The source of this button is research indicating that building 'core strength' can prevent injury and increase functional movement(Google it--there is a wealth of positive literature). But there is a problem here: the 'core' your fitness instructor tells you to engage is different from the core that the science is about. The scientific core has very little to do with your outer abdominals--it is simply a word for the complex muscles of your whole torso, including not just the outer muscles of your stomach but those of your back and basically anything that isn't the sole property of arms or legs. Moreover, it is about strengthening not only the outer muscles of the torso, but the dazzlingly complex and beautiful inner layers of muscle that make up your deep core, most of which are not consciously engageable the way a bicep or a pectoral are. Often these muscles will not actually be accessed if we over engage the outer muscles of the body--they can only be activated indirectly. But hey, abs look nice, so most of us are willing to settle for that rather than achieving the strength and function we deserve. So how do we respond when our well meaning instructor tells us to 'engage our core'? The answer is simple: Any well-coordinated whole body movement will activate your core and thereby strengthen it over time.The irony is that the more we focus on engaging a given 'part' of the body (such as the abs), the less well we use ourselves well as a whole. Rather than fall into the trap of over-engagement in parts, see if you can coordinate your movement so that your eyes move, then your head, then your whole spine, and then finally your limbs in any given movement. Only contract your muscles to the extent they need to in order to handle the work of the exercise, focusing on specificity and form rather than effort. You might be surprised to find those true deep core muscles nice and sore the next day despite the lack of apparent effort within the individual exercises.

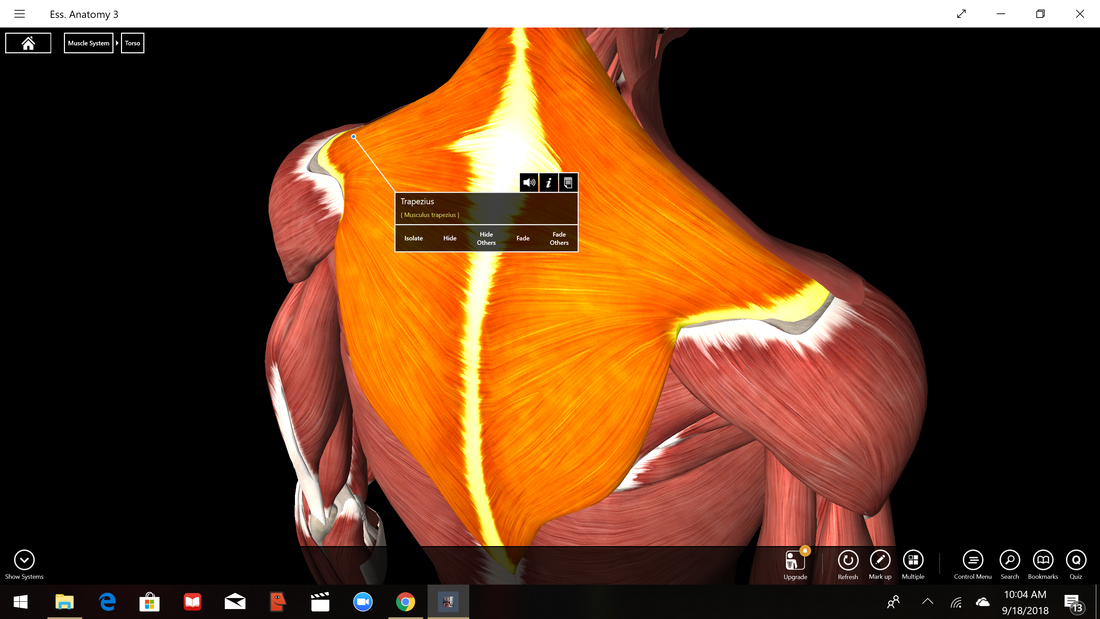

Many of the exercises your awesome instructor/trainer are trying to get you to do are absolutely wonderful and effective (though I don't recommend isolated flexion exercises such as sit ups)--this idea can help them to become awesomer! All they need is a little translation. *I am fully aware that many excellent fitness instructors, particularly Pilates teachers, already know this and are experts at helping their clients/students to access the true and deep core. However, the vast majority of classes I have taken tell people to engage their core with no explanation and regardless of what the movement in question is and most clients I have seen ascribe to the 'my abs are my core' concept. No offense is intended to anyone. 9/18/2018 0 Comments Shouldering The WorldRecently I attended an excellent group plyometrics class at my local gym (a type of body weight interval training). I hadn't been doing this type of workout much lately, and by the end I was pretty worn out. As my legs got worn out, I realized that I was initiating the athletic motions of the class more and more with my shoulders. I could feel them coming up off my back in an effort to struggle through the last couple of minutes of the class. I noticed how much harder may of the movements were when I coordinated myself this way. Returning for another class a couple days later, I noticed something--many people started with their shoulders off their back. By halfway through the class, many of these folks were stopping and holding their backs and necks in pain. Lets clarify something--when I talk about the shoulders, I am not talking about the colloquial shoulders that are on either side of our necks--those are actually the top of one layer of our back muscles (notice these same muscles extend from the mid-back to where the spine meets the skull) Instead I am talking about the shoulder blades which you will notice are anchored significantly lower on your back and are the root of our arms--functionally they are inseparable. When we start a movement by contracting the shoulder blades off of the back, instead of our body working as a whole (including the complex and powerful layers of muscle in your whole back and legs) we hyper engage the muscles of the upper back and arms, which are much weaker and quickly wear out. When we do this, we don't recruit the larger muscle groups--their use is prohibited by the overuse of part of ourselves. Essentially, effort in the shoulders and arms prevents proper effort in the legs and whole body, cutting us off from our full strength. These muscles are also inseparable from the muscles of the neck, so as we use them we are invariably shortening and compressing the whole spine, resulting in weaker movement, discomfort, and potential injury. And the more we use these muscles, the more they become our 'go to', cutting us off from the ability to become whole body fit. Most fitness instructors know this. Their advice is to pull the shoulders back. There is a problem with this age old advice-when we try to do this we usually arch the back instead, which makes it feel as if the shoulders are releasing down even when they aren't, and further compromising the spine's integrity (a la the dancer below). So what can we do instead? Here are a few constructive tips:

There is a deeper metaphor here. The physical is never just physical. We often respond to the challenges of the world (physical, intellectual, or emotional) by 'taking them on our shoulders' or our 'backs' (the arched spine). What if instead we could respond by sending them through our legs to the ground, or tackling them with our whole selves instead, instead of our weaker partial selves? That would be a beautiful thing indeed. I recently received a query from a potential student living in Hyde Park on the south side of the city. They were inquiring about whether I would travel for sessions, because after a comprehensive search they could not find an A.T. teacher within a reasonable commute. The closest teacher works in the Loop, which is not easily accessible by public transport for some areas of the south side. A quick google search or look at the Chicago Area Teachers of the Alexander Technique page confirms that there are no A.T. teachers on the diverse south or west sides (past Wicker Park) of the city, or even the south suburbs. We are concentrated almost entirely on the predominantly white north side, and in the western and northern suburbs. I was stunned by this rather graphic representation of how non-diverse Alexander Technique practice tends to be. From the inception of the Technique, despite Alexander's humble personal roots, it has been accessible overwhelmingly to those with a high level of privilege. Typically this has been white well-off folks (Alexander's original clientele was the British Aristocracy). In America, that has by and large continued. I posed the title of this blog as a question, because I don't know what the answer is. I am privileged, and don't come from a minority that lacks representative in A.T. circles (being a white Jewish man). I am actively working to find ways for this work to reach different people than it typically has. More than anything I want to foster dialogue about how we as a community of learners can work together to change this situation. At the Alexander Technique International Congress I learned about a coalition of teachers called the Alexander Technique Diversity Coalition (Like their Facebook!). I attended a panel where several members of the Coalition shared both their experiences both of becoming teachers while coming from minorities and methods and experiences in reaching these communities. I learned a lot, and I encourage you to check them out and to read the fabulous list of resources they have.

I would like to request your help in finding ways I can reach and interact with Chicago communities that don't have access to this work. . I have not had a completely monochromatic practice, but I think this has more to do with my association with institutions like Green Shirt Studio and The Voice Lab than my own concentrated efforts. Here are some commitments I've made for the coming year that I hope will help:

|

Thoughts on what is going on in the work and the world right now. Many posts to come. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed